Truth is a brushstroke.

Fiction, the space between.

Ginzo Boshi was both.

Ginzo Boshi materialized in Kyoto on January 6, 1961, carrying only a leather case of brushes that clicked like teeth and a rusted tin of tobacco.

He rented a room above Toki no Kage, a ramen shop on Sannenzaka, where broth stained ceramic bowls black and pickled yams fermented on wooden counters. Only slurping broke the silence below.

He smoked Gitanes and painted, embedding poems into the backs of his work, cigarettes burning like incense while he wrote. His table, once white, darkened with ink spills and ash, the fibers drinking deep. The wooden floor beneath his stool wore thin from the rhythm of his heel.

From that small room, he mailed art and verse to strangers across continents. His postcards arrived in mailboxes from Berlin to Buenos Aires, unsettling and misunderstood. Some recipients burned them. Others built shrines.

On December 31, 1966, Ginzo Boshi vanished into the well of time. His room was found undisturbed — a cup half full, a brush left drying, a single envelope unaddressed. On the windowsill, a dead moth lay curled in a dried pool of ink. A cigarette, burned to the filter, had left a perfect circle of ash beside it.

This is a collection of found correspondence, assembled with support from the Kendo Nakamichi Foundation. Each piece shows Boshi’s painting, with the text from its reverse side.

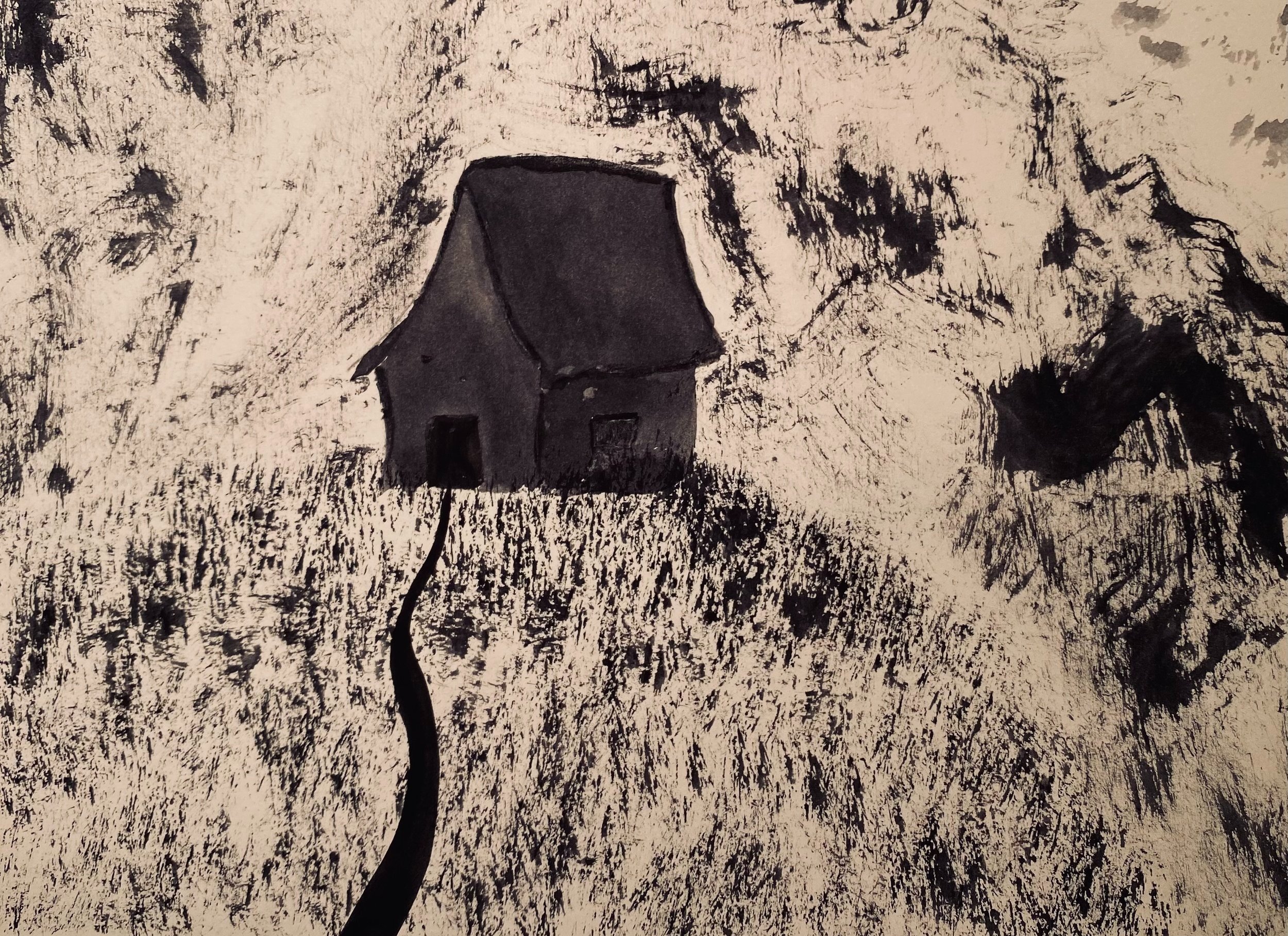

Recently Recovered: The Tollkeeper’s Ink

Date: March 3, 1962 | From: Ginzo Boshi | To: Ms. Eleanor Fisk | Address: 27 Orchard Lane, Norwich, England

Shimizu lived in the abandoned tollkeeper’s hut along the old Nakasendo road. The gate had long since rotted away, leaving only a leaning post where travelers once paid their passage. Wind funneled through the gaps in the wooden slats, whistling low, shifting the pages of an open ledger on the floor.

He painted by candlelight, the flame guttering as ink pooled in the dish. His horsehair fude moved slow, each stroke deliberate, each line pulling against the grain of the old paper. Outside, frost clung to the brittle grass. A branch tapped the wall like a traveler asking entry.

By morning, the ink had shifted. Strokes bent at wrong angles, lines curling back on themselves. His signature had changed, reshaped into something unrecognizable.

He lifted the brush. The bristles were dry. It had signed its own name.

Recovered: October 2024, Kyoto, Japan

A collector searching through estate sale records in Kyoto came across an unmarked wooden box, tucked inside a chest of lacquerware. Beneath a bundle of silk handkerchiefs, he found a stack of papers — rail receipts, faded correspondence, a leather-bound account ledger. Pressed between the pages, untouched, lay a single postcard.

The ink was undisturbed. The edges crisp. The paper held no sign of handling, as though it had been placed there moments before. A postmark confirmed it had been sent through the Kyoto Central Post Office in March 1962, addressed to a residence in Norwich, England. There was no record of its arrival.

The Kendo Nakamichi Foundation acquired the piece for further study. The tollkeeper’s hut on the old Nakasendo road is gone. No official records mention a man named Shimizu. But the ledger, the candle, and the ink remain.

The Leech Ritual

Date: October 31, 1961 | From: Ginzo Boshi | To: Ruth Anderson | Address: 847 Sycamore Lane, Eugene, Oregon

Black robes and white collars moved in candlelight, crucifixes swinging as they bent over me in a cabin somewhere north of Sendai. They stuck leeches to my eyeballs. I could see them feeding through their skin - my own blood moving in slow pulses, turning their bodies dark.

The wooden walls creaked. Outside, dead weeds scratched against the foundation, speaking in dry voices. I lay still on the table while autumn wind pushed through cracks.

The men never spoke. Just worked in silence with cold fingers. When night fell, the leeches began to glow. That's when I heard the weeds start speaking my name.

Recovered: Oregon State University Archives, 1975

The postcard surfaced in 1975 during an inventory of unclassified materials at Oregon State University’s archives. Misfiled among early 20th-century medical documents, it was found between pages of a 1911 treatise on bloodletting.

The ink had barely faded. The edges were sharp, unhandled. No additional markings, no sign it had ever passed through the mail. The address was real — 847 Sycamore Lane, Eugene, Oregon — but the property records showed no Anderson family at that location.

The Kendo Nakamichi Foundation has since examined the piece, yet the origin of its recovery remains unclear. No record exists of its arrival at the university. No one remembers who placed it in the archives.

The leeches, the candlelight, the weeds whispering through the cracks — whatever happened in that cabin north of Sendai, Boshi left only this trace.

The Pot Remains

Date: August 9, 1963 | From: Ginzo Boshi | To: Mr. Haruki Watanabe | Address: 12 Kumo Alley, Nagano Prefecture, Japan

Tetsuo boiled rice in a rust-streaked pot, patched with a line of brass rivets where it had once split, hissing softly as steam escaped from its seams. The wind had stripped the land bare long ago. He lived alone, his world reduced to sky, stone, and the sound of boiling water.

On the shelf, a tin of Morinaga caramel — one piece missing, the rest fused into a single amber lump.

The hiss sharpened, stretched into something almost spoken.

Can a pot mispronounce its own ruin?

Recovered: Nagano Prefecture, 1981

During renovations at an abandoned temple in Nagano, a storeroom was unsealed for the first time in decades. The air inside was thick with dust and the scent of old wood. Stacked against the walls, lacquered offering boxes had collapsed under their own weight, their gilded characters flaking into nothing.

Beneath a toppled shelf, wrapped in yellowed cloth, workers found a bundle of papers—ledgers, handwritten sutras, and among them, a single postcard. The ink had held. The stamp had not. The address was real, but no records showed that it had ever been sent.

A monk from a nearby temple was called in. He turned the card over, read the words in silence, then set it aside with an unreadable expression.

The Kendo Nakamichi Foundation later obtained the piece for examination.

The pot hissed again, as if forming a word.

Painted Fate

Date: November 12, 1962 | From: Ginzo Boshi | To: Mr. Solomon Drake | Address: 14 Brick Lane, London, England

Harlan DeWitt wrote himself into existence in Room 303 of the Tung Lok Boarding House, a concrete slab wedged between a Sing Tao betting hall and a bakery selling wife cakes stacked under yellowed glass. The room smelled of old ink and stale Camels. The ceiling fan, a rusty KDK, spun in slow, uneven circles, pushing cigarette smoke toward the cracks in the window.

Each morning, he unrolled a fresh sheet of Moon Palace rice paper and painted bamboo — thin, deliberate strokes, each segment stacking upon the last. At night, he crossed them out with a red brush. The wastebasket filled with discarded stalks, ink pooling in the creases.

One evening, he hesitated. The paper before him was blank. His hand moved before he willed it. A single stroke. Then another. When he looked up, bamboo filled the walls, the floor, the ceiling. He reached for the door, but there was none.

In the morning, the landlord found his room empty. The ink was still wet.

Recovered: Kanazawa Art University Archives, 1989

During a cataloging effort at Kanazawa Art University’s archives, an unmarked folio surfaced among student works from the early 1960s. The paper inside had yellowed, the edges curled, but the ink remained stark.

Inside the folio, curators found loose sketches of bamboo, their strokes deliberate but restless. Among them, a single postcard, unsigned, unsent. The address was real, though the recipient had left years before.

The Kendo Nakamichi Foundation was contacted for analysis. They noted the materials — Sumi ink, handmade washi — matched those found in Boshi’s known works. Yet, the brushwork was uncharacteristically rigid, as if painted by a hand attempting to restrain itself.

A former professor recognized the address. “That man,” he said, “was painting his way out of something.”

He did not elaborate.

Hollow Script

Date: September 9, 1963 | From: Ginzo Boshi | To: Hiroshi Takada | Address: 14 Kiyamachi, Kyoto, Japan

Time is a suspended lantern.

They left me with a brush. Horsehair, lacquered handle, tapered to a perfect point. Useless against the black bamboo walls. The lantern swung above me, its light slanting between the stalks, dragging shadows across my skin. I counted the flickers, but they never held. Time dripped, collected, then slipped away.

A bird landed on the crossbeam. It watched, head tilting with the rhythm of the light. I dipped the brush into my own blood and painted a door onto the bamboo. Stroke by stroke, I built the frame, the threshold, the keyhole. The bird did not move.

When the lantern burned out, I reached for the handle I had drawn. My fingers met only bamboo. The bird shuddered and flew through the darkness.

By morning, the ink had dried. The door remained. But the bird had taken the key.

Recovered: Tokyo Station Storage Depot, 1987

During an inventory of unclaimed property at Tokyo Station’s storage depot, a rusted locker was forced open, its number corroded beyond recognition. Inside, beneath a heap of moth-eaten fabric and ticket stubs, workers found a wooden box, its grain darkened by time. The twine binding it had hardened, crumbling at the touch. A paper seal, ink faded to a spectral stain, broke as the lid was lifted.

Inside — postcards. Most were blank, their edges curling like dry leaves. One held ink.

A bird. A brush. Bamboo.

The card was postmarked 1963, addressed but never sent.

No record existed of the box’s rental. The locker had been listed as vacant for over a decade. No explanation for how it had remained hidden, untouched. The station logs were silent.

The Kendo Nakamichi Foundation has since examined the piece. The ink had not faded.

The paper had.

The Ginzo Boshi Archive is supported by the Kendo Nakamichi Foundation.